Material systems & sustainable design

2020-03-25

More and more designers want to make material choices that are safer for health and the environment. But a lot of the work that goes into “sustainable design” is about making those kinds of choices possible in the first place.

There’s a prevailing idea that design is the most transformative way to make products and technologies more sustainable—because design is about intentionally shaping how things work, it’s a leverage point where changes can have a big effect on sustainability outcomes. You can change more by redesigning a product than by trying to regulate or control its many environmental impacts. I like this idea, and I use it a lot.

But I’ve found that in the complicated reality of green design—especially where it comes to “designing out” toxic substances—it can still be challenging to move beyond incremental changes. Designers have limited agency to be transformative.

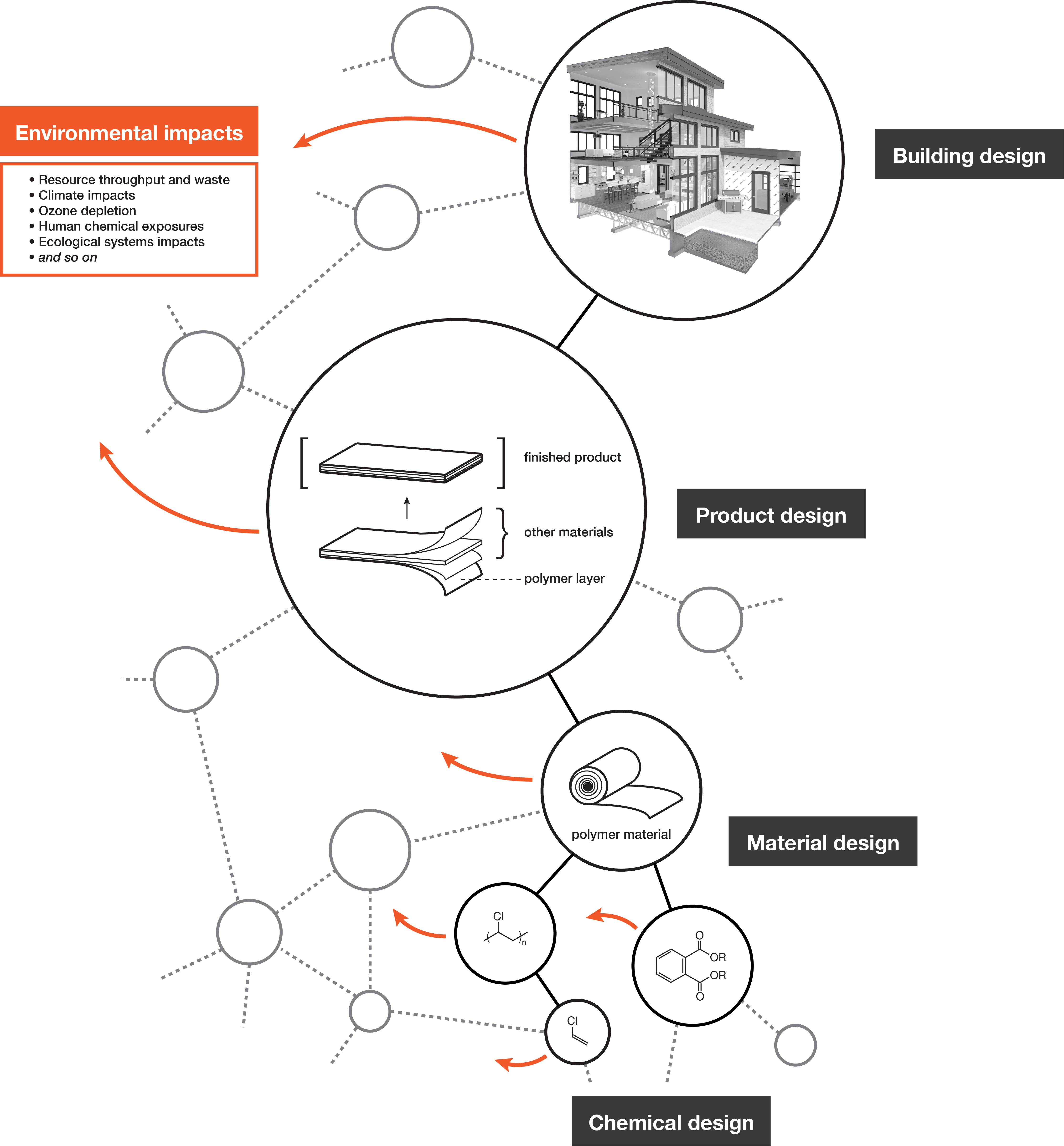

Why? Because our systems of production shape the possibilities for design. The environmental impacts that designers want to reduce or eliminate are the results of a multi-layered network of relationships between chemicals, materials, and other “designed” things. This diagram shows a cross-section of what I mean by a materials system:

Structure

Designers who want to reduce the material life-cycle impacts of buildings have to trace those impacts back to building product design and manufacture, from there to the design and manufacture of industrial materials, and ultimately to the level of chemical design and production.

But designers rarely have the ability to make deep changes that cut across many links in this system, even if that’s what they want to do. The industrial materials system imposes what Dean Nieusma calls “agency-structure tensions,” forces that preserve the status quo against the efforts of interventionist designers. This includes designers’ needs for knowledge and expertise in areas they’re unfamiliar with. But it also includes dominant assumptions about what designers should know and care about, as well as the dominant economic incentives of clients, product manufacturers, and chemical suppliers.

I’ve talked to a number of architects, designers, and engineers whose jobs involve selecting products or materials—choices that will affect people’s homes or workplaces. They take great care to avoid materials that contain toxic substances. To do this, they have to work through the mundane problems that come with this territory: gathering information about what chemicals are used in products or supply chains; researching the health hazards and environmental impacts of different materials or design possibilities. Often it comes down to deciding among limited, imperfect options using uncertain information.

Agency

How can designers push back against these structuring forces? One approach that is playing out in the building sector is collaboration among designers, environmental health NGOs, and scientists. Lisa Goodwin Robbins & colleauges wrote an excellent article about this recently, called “Pruning chemicals from the green building landscape.” Organizations are developing tools to help designers reduce chemical impacts by making informed choices about building products and materials. Pharos, HPD, Declare, and mindful Materials are some examples.

By using these tools, designers can make technical demands on products, materials, and supply chains in ways that were not previously possible—like leveraging disclosure standards to get deeper information about the chemical makeup of products, and holding chemicals to science-based standards of safety. Part of my doctoral research investigated how these “green design tools” help designers to exert new forms of influence through the materials system, while also mediating that influence in subtle ways.

What was this about again?

The point is, to make sustainable design changes within existing technological and material systems—if those systems can even be intentionally changed at all—designers and their collaborators need to mobilize an ever wider variety of resources. Science, tools, standards, policies, market mechanisms, and so on. One way to see this is the field of design practice expanding: like how the chemistry of building materials, which used to be opaque and off-limits to architects and interior designers, is now becoming part of the territory in which they work (at least for some). But the participation of scientists, NGOs, and others also suggests that the boundaries of “design” are fuzzy. Whose intention and agency is it, exactly, that creates green buildings or safer chemicals?

I tell this story to show a picture of “sustainable design” as a complex reality, not just an idea. This emerged from my research as a fragment that I find particularly interesting… and also incomplete. Comments are welcome. Especially from designers.

The graphic above contains an architectural rendering by Wikimedia Commons user Skieridaho, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. My image is therefore also available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.